Future of Regulation in the Life Sciences (hint: AI) and How to Prepare for Change

- Dinesh Agaram

- Mar 29, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 8, 2021

Convergence of Genetics, Medical Devices, Artificial Intelligence, Drug Discovery R&D and Clinical Therapy is happening gradually and is likely to accelerate even more this decade, fuelled by the exponential increase in relevant datasets and sophisticated algorithms to elicit new (and new types of) insights from them.

In practice, this convergence will lead to a deeper interdependence, and therefore, integration, between considerations of Privacy, Accountability, Ethics & Humanity, Intellectual Property Law, Corporate Responsibility and Economics.

At a cross-industry level, biopharma, healthcare, and other allied industries must work together and in tandem to deliver on the potential of this integration, on the promise of patient-centric approaches to drug discovery and care, and on the promise of personalised medicine. Through the revamp of regulation at the intersection of these spheres of human impact, governments and regulatory bodies can enable a significant improvement in effectiveness, decrease in costs, equitability of access, and drastic reduction in time-to-market, as regards new drugs and associated therapies.

As regards Artificial intelligence, the Asilomar Principles are a great set of first principles or axioms to be followed in its development and use. Amongst others, notable ones therein that inform regulatory policy development include those on safety through operational lifetimes, verifiability, explainability with auditability of the explanation by a competent human authority, including the ability to explain any harm caused, rights to personal data, human control over delegation of decisions to AI systems, and planning and mitigation of risks posed by AI systems.

Since much of the convergence noted above will happen due to the opportunity offered by AI and Intelligent Automation, these principles are hugely relevant to future regulation in any industry. If these principles are to be picked up by regulatory authorities for application to the biopharma and healthcare industries, several new regulations may be required.

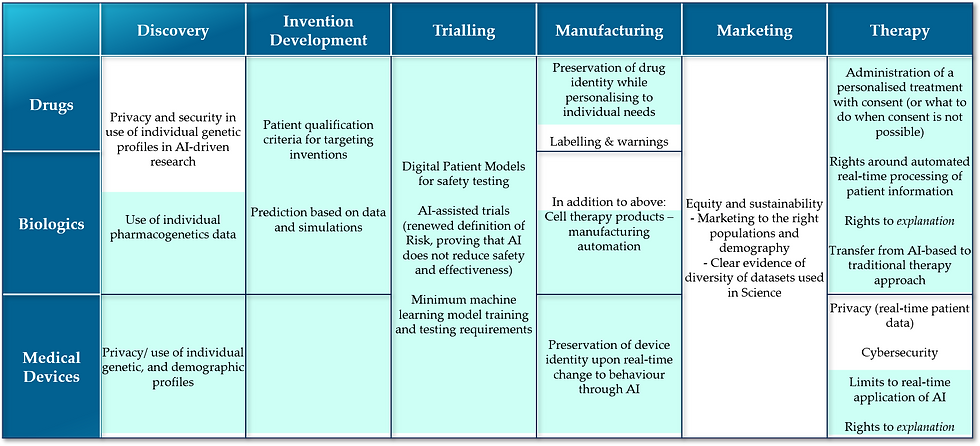

The table below lists some of the new areas of law and regulation one may expect to get developed in different process areas across the medicine-related industries (the European Commission’s current pharmaceutical strategy for Europe is here. The equivalent for USA is here.)

Text in blue background in the above table depicts some of the regulatory aspects that are greatly driven by advancements in AI & Intelligent Automation. Looking at the number of new facets that warrant regulation, it is rather clear that public in the western nations will benefit greatly from a new legal and economic framework to effectively govern healthcare and biopharmaceutical industries, as AI comes of age in them. Converting the framework into a working set of regulations will pose some challenge. I would like to expound below on the framework areas of significant impact to industry and public.

Rights around decisions based on automated real-time processing

Current GDPR regulation in the EU has a provision applying to AI systems which states that a person has the right to not be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her without explicit consent (except in a few limited and exceptional circumstances).

We can nominally expect that in future, the FDA and EMA will take a more nuanced approach to innovations that rely on real-time therapeutic optimisations based on a continuous feedback-response mechanism of drug (or biologic) administration to patients.

This means that in areas where it is not possible or impractical to obtain consent on every decision taken through AI-based methods, regulation may stipulate one or more of the following:

- Give patients a reasonable explanation upfront of how learning aspects of technology behind a therapeutic solution works with patient data, and the potential consequences of the logic applied

o There could also be a stipulation to provide these explanations at every point along the therapy trajectory when a major decision is about to be taken

o Nature of explanation should be unambiguous and complete in terms of characterising potential consequences

- A right to explanation when something goes wrong, to both clinician and patient

- A right to revoke consent to using patient data

- A right to be forgotten – to seek that patient data be disclosed fully to patient and deleted from both clinician and product company’s (drug/device/biologic) databases

- A right to continuous access of the immediate (or recently produced) data that is being used for an AI-based decision

Precision in Modelling

While AI is bound to improve the accuracy of research findings and help overcome the limitations of testing on animals and in test tubes, there is also a huge risk of AI modelling resulting in exactly the opposite, i.e., create artificial environments (for studying the potential effects of drugs) that are laden with biases - hence inherently wrong – potentially leading to cause large-scale unexpected occurrences of severely adverse effects on human subjects. This in a sense is the fundamental risk of AI, and the materialisation of this risk is largely unpredictable.

The success of AI-based medicine is dependent on regulation being able to pre-empt such risk from materialising, both at the R&D stage as well as during the running of a therapy. The following types of regulation or rules within regulation can potentially help make applied AI-based analysis and decision-making in medicine safer:

- Generalisation: establishing similar levels of performance when re-applying or extending a proven logic of drug action for one population segment to new/other segments

- Minimum data requirements for training and re-training of models

- Minimum precision-testing requirements for an individualised treatment by the clinician

- Minimum performance requirements, comparable and perhaps of better standard than human decisions

- Re-testing criteria to prove efficacy and safety of a drug to a new or larger population group

Recourse to non-AI based therapy

While the idea of personalised pharmacogenetics-based approach to medicine that optimises selection (or composition) and dosage of medicine is indeed attractive, risk of outcomes going completely wrong with a limited capability to explain those adverse effects means that patients could legitimately demand a fair recourse to a more trusted mode of therapy. For this to happen, technology systems employed in AI-based therapeutic pathways should possess the ability to provide the right set of information when sought, to help clinicians switch to a non-AI based mode.

Ensuring such a capability could become an essential goal of regulation of AI-based therapies, with stipulations such as:

- Completeness of information required to transfer to a non-AI based therapeutic pathway

- Clinical precautions to be exercised in such transfer of therapeutic approach

- Protocol for exchange of information between biopharmaceutical and healthcare organisations related to such recourse

- Patient consent for change in therapeutic approach

Novel Clinical Trial Designs and Innovation Cycles

Development of robust human atlases and digital patient models will trigger a rapid movement of clinical trials from animal and human subjects to in silico approaches. Even so, we are some distance away from eliminating the need for human subjects in trials. Preclinical and phase 1 trials are the right targets to begin with in application of digital trial models.

However, digital models can also be used for rapid cross-confirmation of drug performance across phases and in actual therapy, could make the prevalent approach to trials sub-optimal in comparison, and perhaps largely redundant. Regulatory authorities may therefore become more open to allowing an agile and iterative approach to the production and marketing of drugs. This may mean a continuous cycle of trials and marketing to increasingly larger target population segments, as more information of performance of drugs against individual genetic profiles becomes available.

Here, the following areas may be ripe for new regulation:

- Continuous oversight rather than periodic analysis and one-time marketing authorisation (full product lifecycle approach to regulation, to facilitate continuous improvement while keeping devices safe and drugs reformulated to cater to different genetic population profiles)

- Data selection and management practices

- Minimum requirements for human subject trials following successful digital trials

- Model training, tuning, validation, monitoring requirements

- Minimum requirements for (extension of) marketing authorisation to newer sub-populations (drug maintenance certification)

PREPARING FOR REGULATIONS RELATED TO AI

To prepare to protect themselves fully and conform to potential regulation, and to simultaneously make the most of the potential of AI, there are common strategies that every player in the healthcare and drug discovery ecosystem can adopt:

· Investing in developing TRACEABILITY capability: providing any kind of explanation of how a drug works on an individual or a sub-population, either to patients, clinics or regulators, requires relevant information about PK/PD and pharmacogenetics applied in invention. Whether it is information collected through human subjects or simulated through digital patient models, traceability through the innovation and therapy process will be required to achieve explainability

· Developing HIGH QUALITY DATA and ACCURATE DIGITAL MODELS: this is a prerequisite to tailor a drug to effectively counter a condition in a patient or sub-population of patients and make precision medicine possible, whether it is about disease contextualisation and characterisation or about patient population characterisation

· Developing DATA INTEGRATION PARTNERSHIPS actively across the eco-system: to make end-to-end real-time integration of the ecosystem possible, which in turn will give a chance to access right data sets, have access to real-time data, and effect an iterative and agile approach to improving the quality to drugs and therapies, and being able to optimise them for population segments and individual patients

· Developing ORGANISATIONAL RESPONSIVENESS: While regulation is likely to continue to focus on safety and effectiveness while supporting AI’s incorporation, it is also likely to expect quick turnaround from organisations in addressing exigent situations and adverse events making use of cross-industry and cross-organisational integrations. Implementing business processes and organisational structures that are flexible and responsive will help organisations implement regulatory requirements in quick time

· Practicing and perfecting ACCOUNTABILITY: Confidence of patients and governments (including regulatory bodies) in AI-based approaches will improve when those stakeholders can see clearly that data is being used safety and securely, and that transparency is being practiced well.

Conclusion

Pharmaceutical and healthcare regulation in the western world has made great strides in the last couple of decades in enabling the use of data in a safe manner in both trialling and therapy processes. The potential though is immense and the exponential increase in both feedback and real-time data availability necessitates a new regulatory framework that can further enable industry in making use of advancements in Artificial Intelligence and Intelligent Automation. This regulatory framework should enable both the rapid testing and accurate generalisation of drug applicability to larger populations and at the same time improve the information required to develop tailored drug products to smaller population targets and individuals (precision/personalised medicine).

AI implementations, while promising to assume delegated responsibility over intuition and probabilistic thinking and judgment from their human counterparts, are not culpable entities when something goes wrong. The responsibility of society, corporates and governments is still human-to-human, i.e., regulation of AI is still in a sense regulation of humans and what they do with AI to address human issues. Making humans answerable to the consequences of dynamic, responsive decision-making of AI is a big challenge for regulation. In this, automation, precision modelling, clinical trial design and on-the-fly risk assessment, changing identities of devices and changing treatment pathways offer a convergent space that could be subject to substantial changes to current regulation and advent of new regulation.

To be prepared to thrive and effect favourable outcomes to public health and the economy making use of the data-driven convergence, AI and enabling new regulation, actors in the ecosystem need to work individually and together to build trust in their stakeholders, reconfigure into responsive organisations, and invest in developing the following: high quality data assets, accurate digital models (especially biological), data integration partnerships and traceability of decisions (both automated and non-automated).

Comments